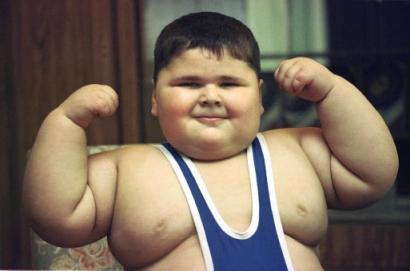

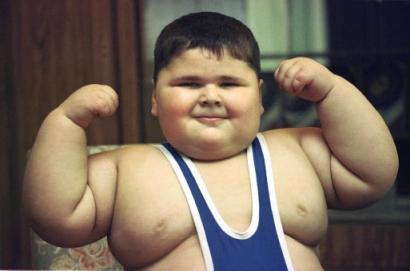

As nearly all of my posts preceding this one have indicated, the brain exists in a constant state of equilibrium, striking a variable balance between responses to internal and external environmental conditions. A recent article published by one of our very own fellow Duke students, Krishnan Patel, outlines the role of an eating disorder as a sort of dysregulation of this dynamic equilibrium, in which skewed self-perception and and food-based rewards create a psychopathological disorder characterized by periods of overindulgence in food without the existence of following purging behavior. A study by Schienle et al. in 2009 uses fMRI to attempt to establish a neurobiological relationship between the response to food stimuli and BED (binge-eating disorder) by monitoring the brain activation of patients while they are being presented with food. The results yielded the finding of increased activation in the medial orbito-frontal cortex in BED patients in response to food presentation. Furthermore, the medial OFC is thought to be responsible for the attribution of varying value to stimuli as well as multisensory integration; it then uses that information to make and execute decisions. However, a short-coming of this study is the fact that only a visual representation of food stimuli were utilized. Therefore the neural response very well might have been slightly off than the response that would be recorded from the presentation of actual food (although that presentation in itself would pose the issue of presenting multiple sensory stimuli including smell).

As nearly all of my posts preceding this one have indicated, the brain exists in a constant state of equilibrium, striking a variable balance between responses to internal and external environmental conditions. A recent article published by one of our very own fellow Duke students, Krishnan Patel, outlines the role of an eating disorder as a sort of dysregulation of this dynamic equilibrium, in which skewed self-perception and and food-based rewards create a psychopathological disorder characterized by periods of overindulgence in food without the existence of following purging behavior. A study by Schienle et al. in 2009 uses fMRI to attempt to establish a neurobiological relationship between the response to food stimuli and BED (binge-eating disorder) by monitoring the brain activation of patients while they are being presented with food. The results yielded the finding of increased activation in the medial orbito-frontal cortex in BED patients in response to food presentation. Furthermore, the medial OFC is thought to be responsible for the attribution of varying value to stimuli as well as multisensory integration; it then uses that information to make and execute decisions. However, a short-coming of this study is the fact that only a visual representation of food stimuli were utilized. Therefore the neural response very well might have been slightly off than the response that would be recorded from the presentation of actual food (although that presentation in itself would pose the issue of presenting multiple sensory stimuli including smell).

Thursday, February 24, 2011

The Underlying Mechanism of Binge Eating

As nearly all of my posts preceding this one have indicated, the brain exists in a constant state of equilibrium, striking a variable balance between responses to internal and external environmental conditions. A recent article published by one of our very own fellow Duke students, Krishnan Patel, outlines the role of an eating disorder as a sort of dysregulation of this dynamic equilibrium, in which skewed self-perception and and food-based rewards create a psychopathological disorder characterized by periods of overindulgence in food without the existence of following purging behavior. A study by Schienle et al. in 2009 uses fMRI to attempt to establish a neurobiological relationship between the response to food stimuli and BED (binge-eating disorder) by monitoring the brain activation of patients while they are being presented with food. The results yielded the finding of increased activation in the medial orbito-frontal cortex in BED patients in response to food presentation. Furthermore, the medial OFC is thought to be responsible for the attribution of varying value to stimuli as well as multisensory integration; it then uses that information to make and execute decisions. However, a short-coming of this study is the fact that only a visual representation of food stimuli were utilized. Therefore the neural response very well might have been slightly off than the response that would be recorded from the presentation of actual food (although that presentation in itself would pose the issue of presenting multiple sensory stimuli including smell).

As nearly all of my posts preceding this one have indicated, the brain exists in a constant state of equilibrium, striking a variable balance between responses to internal and external environmental conditions. A recent article published by one of our very own fellow Duke students, Krishnan Patel, outlines the role of an eating disorder as a sort of dysregulation of this dynamic equilibrium, in which skewed self-perception and and food-based rewards create a psychopathological disorder characterized by periods of overindulgence in food without the existence of following purging behavior. A study by Schienle et al. in 2009 uses fMRI to attempt to establish a neurobiological relationship between the response to food stimuli and BED (binge-eating disorder) by monitoring the brain activation of patients while they are being presented with food. The results yielded the finding of increased activation in the medial orbito-frontal cortex in BED patients in response to food presentation. Furthermore, the medial OFC is thought to be responsible for the attribution of varying value to stimuli as well as multisensory integration; it then uses that information to make and execute decisions. However, a short-coming of this study is the fact that only a visual representation of food stimuli were utilized. Therefore the neural response very well might have been slightly off than the response that would be recorded from the presentation of actual food (although that presentation in itself would pose the issue of presenting multiple sensory stimuli including smell).

Adolescent Risk-Taking

A recent study published in ScienceDirect, conducted by Steinberg et al., proposes a framework for theory and research on developmental risk-taking They explore the two following questions:

1. Why does risk-taking increase between childhood and adolescence?

2. Why does risk-taking decline between adolescence and adulthood?

This study ultimately shows that the initial increase in risk-taking is the result of the brain's socio-emotional system leading to an increased desire in reward, especially in the presence of friends or in social situations. This desire is fueled by the significant remolding of the brain's dopaminergic system during and throughout puberty. The decline of adolescent risk-taking occurs when the brain's cognitive control system develops even further, increasing individual capacity for self-regulation and, essentially, common sense or a higher regard for safety over social reward. The changes are mirrored by visible and functional changes in the prefrontal cortex as well as its connection to other important brain regions. For all of the reasons cited above, mid-range adolescence has been proven to be the time for highest risky and reckless behavior.

To view the full Steinberg et al. article, follow this link.

1. Why does risk-taking increase between childhood and adolescence?

2. Why does risk-taking decline between adolescence and adulthood?

|

| Mature Prefrontal Cortex Activity |

This study ultimately shows that the initial increase in risk-taking is the result of the brain's socio-emotional system leading to an increased desire in reward, especially in the presence of friends or in social situations. This desire is fueled by the significant remolding of the brain's dopaminergic system during and throughout puberty. The decline of adolescent risk-taking occurs when the brain's cognitive control system develops even further, increasing individual capacity for self-regulation and, essentially, common sense or a higher regard for safety over social reward. The changes are mirrored by visible and functional changes in the prefrontal cortex as well as its connection to other important brain regions. For all of the reasons cited above, mid-range adolescence has been proven to be the time for highest risky and reckless behavior.

To view the full Steinberg et al. article, follow this link.

The Consciousness Question: a Social Neuroscientific Approach

The topic of consciousness has never departed from the discussion of the philosophy of the mind. However, with the development of the neurosciences and the flooding of general neuroscientific discoverines, philosophical debates about the nature of consciousness have taken a turn towards physicalism.

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy cites several researchers concerned with the consciousness question, most notable among whom are Thomas Nagel, David Chalmers, and Paul & Patricia Churchland. The first of these philosophers clings to the inexplicable nature of consciousness, claiming that the experience is solely subjective and therefore forever elusive to the constraints of objective scientific understanding. Chalmers, on the other hand, offers a bit more room for interpretation in his conceptual version of consciousness. He describes consciouisness as any brain process, but that this brain process with inevitably leave open an 'explanatory gap' that differentiates the brain processes from the conscious experiences themselves. For example, a brain process might include read a line of text and interpreting that line of text as our brain is programmed to do; however, the feeling we experience when we read that text -- the intangible emotion or sensation that defines that text, and makes that special at an individual level -- that feeling cannot be allotted solely to neural processes.

Lastly, the Churchlands develop a strictly neuroscientific approach to consciousness, which is based upon the recurrent connections between thalamic nuclei and the cortex. They assert that the selective features that comprise the 'core' of the human conscious experience are the result of thalamacortical recurrency. Patricia Churchland specifically references philosophical implications of a variety of neurological deficits to evince the concept of a 'unity of self' -- a tenet of human consciousness. She uses deficits such as blindsight -- a deficit in which patients are unable to see items in specific regions of their visual fields -- to prove this unity of self, by demonstrating that individuals with blindsight still perform far better than chance in forced guess trials about stimuli in blindsight regions.

However, I'd like to offer a slightly different perspective on human consciousness. After having read several articles on neuroscience, social neuroscience, and philosophy of the mind, I would like to posit the notion that a distinct measure of human consciousness is defined by social interactions. Much of the philosophies I've encountered that discuss the consciousness question neglect to account for the undeniable role of social interactions in our neural processes. My version of human consciousness fuses the physicalism of the Churchlands with an attempted response to Chalmers' 'explanatory gap.' This explanatory gap, in my view, is accounted for by the random, intangible, and unpredictable social experiences and lessons each individual has accumulated throughout his or her life. Using the same example I cited above--in which you read a line of text as your brain is programmed to read it, yet you interpret it and feel a certain way about it--I propose that this intangible sensation is the result of a learned behavioral and neural response that each of us has gained through various interpersonal or personal experiences.

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy cites several researchers concerned with the consciousness question, most notable among whom are Thomas Nagel, David Chalmers, and Paul & Patricia Churchland. The first of these philosophers clings to the inexplicable nature of consciousness, claiming that the experience is solely subjective and therefore forever elusive to the constraints of objective scientific understanding. Chalmers, on the other hand, offers a bit more room for interpretation in his conceptual version of consciousness. He describes consciouisness as any brain process, but that this brain process with inevitably leave open an 'explanatory gap' that differentiates the brain processes from the conscious experiences themselves. For example, a brain process might include read a line of text and interpreting that line of text as our brain is programmed to do; however, the feeling we experience when we read that text -- the intangible emotion or sensation that defines that text, and makes that special at an individual level -- that feeling cannot be allotted solely to neural processes.

Lastly, the Churchlands develop a strictly neuroscientific approach to consciousness, which is based upon the recurrent connections between thalamic nuclei and the cortex. They assert that the selective features that comprise the 'core' of the human conscious experience are the result of thalamacortical recurrency. Patricia Churchland specifically references philosophical implications of a variety of neurological deficits to evince the concept of a 'unity of self' -- a tenet of human consciousness. She uses deficits such as blindsight -- a deficit in which patients are unable to see items in specific regions of their visual fields -- to prove this unity of self, by demonstrating that individuals with blindsight still perform far better than chance in forced guess trials about stimuli in blindsight regions.

However, I'd like to offer a slightly different perspective on human consciousness. After having read several articles on neuroscience, social neuroscience, and philosophy of the mind, I would like to posit the notion that a distinct measure of human consciousness is defined by social interactions. Much of the philosophies I've encountered that discuss the consciousness question neglect to account for the undeniable role of social interactions in our neural processes. My version of human consciousness fuses the physicalism of the Churchlands with an attempted response to Chalmers' 'explanatory gap.' This explanatory gap, in my view, is accounted for by the random, intangible, and unpredictable social experiences and lessons each individual has accumulated throughout his or her life. Using the same example I cited above--in which you read a line of text as your brain is programmed to read it, yet you interpret it and feel a certain way about it--I propose that this intangible sensation is the result of a learned behavioral and neural response that each of us has gained through various interpersonal or personal experiences.

Social Intelligence & fMRI: Normal vs. Autistic/Asperger Brain

|

| Simon Baron-Cohen |

Apart from general intelligence, there exists the theory of social intelligence, first proposed by primatologist Brothers. She proposed social intelligence as the "ability to interpret others' behavior in terms of mental states, to interact both in complex social groups and in close relationships, to empathize with others' states of mind, and to predict how others will feel, think, and behave." She further posited that the amygdala, orbito-frontal cortex (OFC), and superior temporal gyrus (STG) were the central neural correlates to social intelligence.

The fMRI studies confirmed Brothers' prediction that the STG and amygdala show increased activity when participants used 'social intelligence' to interpret eye expressions. Meanwhile, the patients with autism or AS activated fronto-temporal regions instead of the amygdala, leading them to make mentalistic judgements devoid of emotional comprehension. Ultimately, this study provides evidence for Brothers' theory of social intelligence. However, I am inclined to question the comprehensive validity of fMRI scans in general, due to the lack of temporal accuracy of the scans.

Psychosis and Hearing Impairment: a Link in Adolescence

Much of modern medical, psychiatric literature is in agreement that highest rates of psychotic behavior occur in adolescents and young adults. Yet, a particular subset of this literature provides evidence for a link between adolescent hearing impairment and increased risk for psychosis. A recent study published in Psychological Medicine explored the possibility of adolescent development of psychosis as an outcome of hearing impairment. The van der Werf et al. research team documented a ten-year long longitudinal study of 3,021 adolescents aged 14-24 years old. The group hypothesized that individuals exposed to hearing impairment in adolescence would be at highest risk of developing psychotic symptoms during their progression into adulthood. They launched the cohort study outlined above and assessed psychosis expression at multiple time points over the duration of 10 years, using a diagnostic interview administered by a team of professional clinical psychologists. These interviews provide a means of measuring psychosis expression by assessing symptoms, syndromes, and diagnoses of various mental disorders; furthermore, the interviews allow for self-reported symptoms throughout the 10 years of the study.

This study yielded the finding that hearing impairment was in fact associated with psychotic symptoms, with an odds ratio of 2.04 (a 2:1 chance of expressing psychotic symptoms as an adolescent with hearing impairment). Furthermore, subjects between ages 14 and 17 exhibited even higher levels of psychosis expression, with self-reported experiences like delusional thinking and hallucinations. This finding suggests that perhaps the social and personal vulnerabilities that accompany adolescent hearing loss disrupt a critical phase in development, causing the observed increased in psychotic symptoms throughout adulthood development.

Although I find the implications of this article fascinating, I do wish that van der Werf et al. had further delved into which specific social interactions and events throughout these individuals adolescence had made those patients with adolescent hearing loss more prone to psychosis. After having read the previous article I posted in my blog, it is clear to me that that is an undeniable connection with behavioral/neural plasticity in response to social events, and I believe that much of this is in play when considering individuals whose adolescent developments have been so altered by hearing impairment at such a young age.

This study yielded the finding that hearing impairment was in fact associated with psychotic symptoms, with an odds ratio of 2.04 (a 2:1 chance of expressing psychotic symptoms as an adolescent with hearing impairment). Furthermore, subjects between ages 14 and 17 exhibited even higher levels of psychosis expression, with self-reported experiences like delusional thinking and hallucinations. This finding suggests that perhaps the social and personal vulnerabilities that accompany adolescent hearing loss disrupt a critical phase in development, causing the observed increased in psychotic symptoms throughout adulthood development.

Although I find the implications of this article fascinating, I do wish that van der Werf et al. had further delved into which specific social interactions and events throughout these individuals adolescence had made those patients with adolescent hearing loss more prone to psychosis. After having read the previous article I posted in my blog, it is clear to me that that is an undeniable connection with behavioral/neural plasticity in response to social events, and I believe that much of this is in play when considering individuals whose adolescent developments have been so altered by hearing impairment at such a young age.

'Social Defeat' Stressors & Behavioral Plasticity

An emerging field of social neuroscience explores the correlation between neural and behavioral plasticity. One might say that there is a particular 'zone' associated with this correlation: the mesolimbic dopamine pathway. This pathway, along with its projections into the nucleus accumbens, allows an organism to create automatic associations between emotionally salient stimuli in the environment and their outcomes, so that the organism can approach or avoid the stimuli accordingly--almost like a computer program that returns a particular output for a given input. A study by research team Berton et al. observes the effects of repetitive 'social defeat stress' in order to examine which exact neural correlate mediates long-term neural and behavioral plasticity in response to aversive social experiences. First, the team had to characterize the molecular mechanism responsible for altering activity in the mesolimbic dopamine pathway in response to a particular psychosocial experience. In order to do this, they adopted an experimental paradigm that models 'social defeat,' in which various mice were exposed to a different aggressor mouse each day for 10 days, and the social approach toward an unfamiliar mouse was recorded in a wire mesh cage that utilized a video-track system to track the 'socially defeated' mice's movement.

As you can see in the image on the left, the mice subjected to 'social defeat' generally avoided the interaction zone, where it would interact with each new aggressor mouse. These mice therefore developed an aversion to social interaction, signaling unified neural and behavioral plasticity in response to a negative social experience. Further gene profiling/mainuplation of the subjects' NAc (nucleus accumbens) yielded the finding that brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is responsible for both the development of experience-developed social aversion and the obliteration of this aversion, thus indicating the integral role of BDNF in modulating neural and behavioral plasticity in response to negative social experiences.

As you can see in the image on the left, the mice subjected to 'social defeat' generally avoided the interaction zone, where it would interact with each new aggressor mouse. These mice therefore developed an aversion to social interaction, signaling unified neural and behavioral plasticity in response to a negative social experience. Further gene profiling/mainuplation of the subjects' NAc (nucleus accumbens) yielded the finding that brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is responsible for both the development of experience-developed social aversion and the obliteration of this aversion, thus indicating the integral role of BDNF in modulating neural and behavioral plasticity in response to negative social experiences.

To view the full Berton et al. study, follow this link.

To view the full Berton et al. study, follow this link.

Long-Term Effects of Maternal Separation During Infancy

As a follow-up to one of my previous posts regarding the long-term effects of variations in maternal care on learning abilities of offspring, I chose to explore the long-term effects of maternal absence or separation on offspring and development. This led me to a study conducted by Romeo et al., which utilized open-field tests and elevated-plus maze tests to measure how fear/anxiety behaviors in adult mice were effected by maternal separation during infancy. This video below gives a sense for what exactly occurs during an open-field test.

Several previous studies suggest negative consequences in adulthood that result from physical and emotional neglect in childhood. This negative consequences include a higher likelihood to develop anxious or depressive behaviors in adulthood. Thus, the Romeo et al. study explores the lasting influence of early-life stressors on adulthood behaviors. They examined both males and females and, interestingly, found very different effects of MS (maternal separation) with respect to the sex of the subject. In male mice that experienced MS in the neonatal period, open-field tests and elevated-pus maze tests indicated that these male mice displayed significantly higher levels of anxiety and fear behaviors then those of the control mice. On the other hand, female mice that underwent the same tests displayed reduced anxiety and fear behaviors, however the females only demonstrated this reduction of anxiety/fear during the diestrous phase of their estrous cycle.

Ultimately, these results indicate that maternal separation can determine emotionality of adult male and female mice; however the degree and expression of this effects depends upon both the SEX and the PHASE of the estrous cycle of the female subject.

To view the full Romeo et al. article, follow this link.

Several previous studies suggest negative consequences in adulthood that result from physical and emotional neglect in childhood. This negative consequences include a higher likelihood to develop anxious or depressive behaviors in adulthood. Thus, the Romeo et al. study explores the lasting influence of early-life stressors on adulthood behaviors. They examined both males and females and, interestingly, found very different effects of MS (maternal separation) with respect to the sex of the subject. In male mice that experienced MS in the neonatal period, open-field tests and elevated-pus maze tests indicated that these male mice displayed significantly higher levels of anxiety and fear behaviors then those of the control mice. On the other hand, female mice that underwent the same tests displayed reduced anxiety and fear behaviors, however the females only demonstrated this reduction of anxiety/fear during the diestrous phase of their estrous cycle.

Ultimately, these results indicate that maternal separation can determine emotionality of adult male and female mice; however the degree and expression of this effects depends upon both the SEX and the PHASE of the estrous cycle of the female subject.

To view the full Romeo et al. article, follow this link.

Depression: Efforts to Determine the Neural Correlate

The efficacy of anti-depressant medications (ADs) has been a prevalent topic of discussion amongst cellular biologists and neuroscientists alike since the development of the drugs themselves. Particularly, researchers have been searching tirelessly to determine the precise neural correlate of depressive behaviors. The only unambiguous finding of this search has been the association of a marked increase in hippocampal neurogenesis that accompanies chronic AD treatments; however, researchers have been unable to directly pinpoint the functional significance of this activity. Thus, in order to identify the functional importance of increased hippocampal neurogenesis in response to chronic AD medication, Santarelli et al. examined the effects of radiological disruption of anti-depressant-induced hippocampal neurogenesis. The team performed X-irradiation on only the hippocampus of mice using a lead plate to direct the signal. The X-irradiation deactivated the neurogenic effect of the chronic AD medication, yielding no behavioral response to the ADs. Thus, Santarelli et al. found that disrupting this hippocampal neurogenesis entirely blocked any behavioral response to the anti-depressant medications, making the mice unresponsive to the ADs and nulling the functionality of the treatment.

The efficacy of anti-depressant medications (ADs) has been a prevalent topic of discussion amongst cellular biologists and neuroscientists alike since the development of the drugs themselves. Particularly, researchers have been searching tirelessly to determine the precise neural correlate of depressive behaviors. The only unambiguous finding of this search has been the association of a marked increase in hippocampal neurogenesis that accompanies chronic AD treatments; however, researchers have been unable to directly pinpoint the functional significance of this activity. Thus, in order to identify the functional importance of increased hippocampal neurogenesis in response to chronic AD medication, Santarelli et al. examined the effects of radiological disruption of anti-depressant-induced hippocampal neurogenesis. The team performed X-irradiation on only the hippocampus of mice using a lead plate to direct the signal. The X-irradiation deactivated the neurogenic effect of the chronic AD medication, yielding no behavioral response to the ADs. Thus, Santarelli et al. found that disrupting this hippocampal neurogenesis entirely blocked any behavioral response to the anti-depressant medications, making the mice unresponsive to the ADs and nulling the functionality of the treatment.This study provides evidence for the notion that neurogenesis in the hippocampus is strongly-correlated to the behavioral effects of chronic anti-depressant treatment. Essentially, this indicates that chronic AD treatment MUST stimulate hippocampal neurogenesis, and without this stimulation, the behavioral response to chronic AD treatment will be nullified. Therefore, neurogenesis in the hippocampus is integral to the efficacy of chronic anti-depressant treatments, and these results are extremely significant because human beings respond most to chronic --not acute-- AD treatments.

To view the Santarelli article, follow this link.

Maternal Care & Learning Capabilities of Offspring

A recent study by Dong Liu et al. utilized rat mothers and their litters to examine a potential correlation between variation in types of maternal care with variation in related offsprings' cognitive abilities. This study offers a comparison between two types of mothering. The first type of mothering, which I will refer to as Type 1, is characterized by an elevated level 'hands-on' attention: a Type 1 mother engages in frequent licking, frequent grooming, and arched-back nursing of the pups in her litter. A Type 2 mother exhibits a lesser level of 'hands-on' attention: less frequent licking, grooming, and nursing of her pups. At this point I would like to make clear that there is of course a range of mothering types; there are several more than Type 1 and Type 2, however for the purposes of this study and of clarity, I will describe mothering types in this binary manner. The Liu et al. research team ultimately found variations at the neuronal level that varied with respect to the type of mothering with which the offspring were raised. Offspring of Type 1 mothers exhibited markedly different activity at the neuronal level, with increased expression of NMDA receptor subunit and BDNF mRNA. Although this sounds overly-complex, what this finding truly means is that offspring of Type 1 mothers displayed increased innervation of the hippocampus, and it is this increased innervation that Liu et al. has deemed the differentiating factor between the offspring of Type 1 versus Type 2 mothers.In particular, this variation in hippocampal development is associated with enhanced spatial learning and memory capabilities. Therefore, offspring of Type 1 mothers became 'wired' to exhibit an enhanced level of spatial learning and memory, while Type 2 offspring simply did not demonstrate the same capabilities.

The results of this study suggest that variations in maternal care can create correlative variations in neural function at the molecular level--at the very core of neural learning processes. Hands-on maternal care in mice created enhanced learning capabilities in offspring due to increased innervation of the hippocampus. Alternatively, mothers with low-frequency care raised offspring who did not demonstrate the same level of cognitive learning abilities. These observations should be quite indicative of similar responses in human maternal interaction; however the certainty of the correlation can not be unquestionably determined without a human study.

To view the Liu et al article, follow this link.

| Neuron density and cell field volume in various parts of the hippocampus |

The results of this study suggest that variations in maternal care can create correlative variations in neural function at the molecular level--at the very core of neural learning processes. Hands-on maternal care in mice created enhanced learning capabilities in offspring due to increased innervation of the hippocampus. Alternatively, mothers with low-frequency care raised offspring who did not demonstrate the same level of cognitive learning abilities. These observations should be quite indicative of similar responses in human maternal interaction; however the certainty of the correlation can not be unquestionably determined without a human study.

To view the Liu et al article, follow this link.

Tuesday, February 22, 2011

Deception: is there a neural activation pattern associated with truth inhibition?

The Langleben et al. article "Brain Activity during Simulated Deception: An Event-Related Functional Magnetic Resonance Study" supports the existence of a link between deception and a corresponding neural activation pattern. Initially, researchers questioned the possibility of identifying a difference in neural activity when lying and telling the truth using fMRI brain imaging. They then questioned whether or not this activity would indicate truth inhibition in the prefrontal cortex and cingulate. These inquiries led to a laboratory adaptation of the Guilty Knowledge Test (GKT), involving twenty-three participants, each of whom received an envelope containing a $20 bill and a 5 of Clubs playing card. Each participant was told that he or she would be able to keep the $20 bill if able to successfully belie his or her card’s identity from a computer—the MRI scanner—that would ask the questions: “Do you have this card?” and “Is this the 10 of Spades?”. Here, the 10 of Spades operated as the Control card. The participants were encouraged to lie only about the identity of the 5 of Clubs, reducing anxiety-induced brain activity. Key results include neural-imaging evidence of truth inhibition as illustrated by elevated levels of right ACC activation when lying. This result follows a response inhibition archetype that deems the ACC as a monitor for conflicting responses, which means that right ACC activation indicates the site where the option to tell the truth was processed and then shut down in favor of lying. Furthermore, an increase in motor activation when lying about possessing the 5 of Clubs indicates a physical effort associated with truth inhibition, suggesting that truth is the natural cognitive inclination, and that one must first shut down this primary response before being able to lie.

This increase in BOLD fMRI signal indicates that the difference between lying and telling the truth on the GKT can be detected and localized using BOLD fMRI. Also, although tentative, the lack of participant anxiety implies a disconnect between ACC activation and anxiety during deception, further proving the unreliability of the traditional polygraph. Ultimately, the results of this study evince the existence of a traceable neural activation pattern associated with deception.

Langeleben et al (2002). Brain Activity during Simulated Deception: An Event-Related Functional Magnetic Resonance Study. NeuroImage 15, 727–732 (2002).

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)